Reading Guide

Two main reading paths

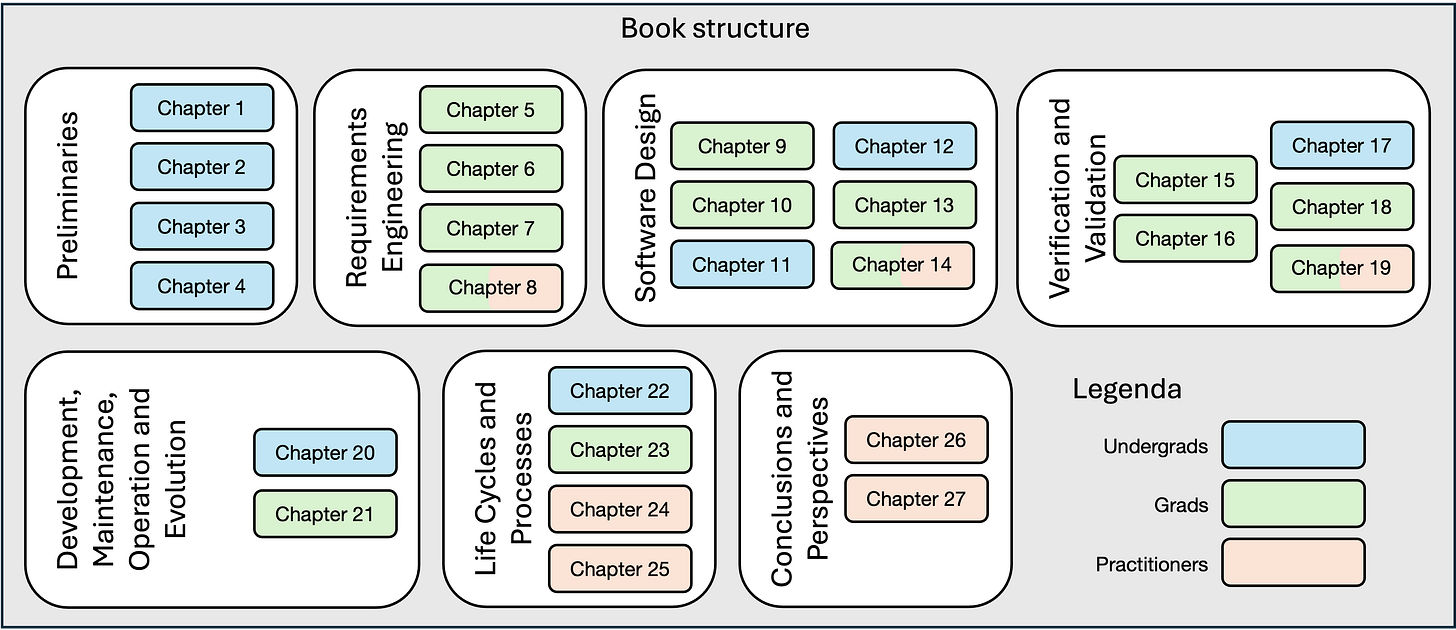

The book is structured to accommodate multiple reading approaches. Readers may choose to progress sequentially from beginning to end, concentrate on specific parts, or navigate across chapters according to their interests and the depth of understanding they seek.

Drawing on our experience teaching both the bachelor-level Software Engineering course and the master-level Software Engineering 2 course at Politecnico di Milano, we recommend the following two reading paths (see the figure above):

Undergraduate entry-level course on Software Engineering: Bachelor-level students are encouraged to concentrate on the foundational principles of the discipline, beginning with the nature of software products, the software development life cycle, and the role of modeling (Chapters 1, 2, and 3). They should gain familiarity with UML as a standard modeling language (Chapter 4), and explore software process models (Chapter 22). Core topics in software design for small- to medium-scale systems should also be studied (Chapters 11 and 12), along with the essential concepts of software verification and testing (Chapter 17). Finally, they should acquire a practical understanding of the tools and practices that support the coding phase (Chapter 20).

Graduate-level course in Software Engineering: Master-level students should concentrate on topics central to the development of complex, long-lived software systems. Their learning begins with a deep understanding of requirements engineering, emphasizing the importance of analyzing both the system’s intended functionality and its operational context (Chapter 5). This includes mastering techniques for eliciting stakeholder needs (Chapter 6) and systematically formulating clear, analyzable requirements (Chapter 7). The focus then shifts to software design, with particular attention to software architecture (Chapter 9). Students are introduced to architectural styles (Chapter 10) as reusable design solutions for recurring problems and explore how architectural tactics can be applied to improve key quality attributes (Chapter 13). Additionally, they will learn how to assess architectural choices through structured evaluation methods.

Verification and validation (V&V) form the next essential area of study. Students begin with an overview of the V&V processes (Chapter 15) and then explore static analysis techniques (Chapter 16) and automated testing strategies (Chapter 18) to ensure software reliability.

To reinforce the practical application of these principles, the book provides an integrated case study spanning the main development phases—from requirements engineering through design to verification and validation (Chapters 8, 14, and 19).

Given the long-term nature of many software systems, students are also encouraged to study the principles of software operation, maintenance, and evolution (Chapter 21). Lastly, to prepare for collaborative, real-world development settings, students should become familiar with project management concepts and the challenges associated with planning, coordination, and delivery in large-scale software projects (Chapter 23).

Finally, practitioners and software engineering experts can take advantage from reading Chapter 21 focusing on operation, maintenance and evolution, Chapter 24 introducing the reader to open-source software and its benefits and challenges, Chapter 25 presenting the importance of continuous software process improvement and the practices that can be adopted, and Chapter 26 offering an overview of the interplay between generative AI and software engineering.